The Rauch Report

By Bill Rauch

As we approach Edward de Vere’s 465th birthday, we approach also a reevaluation of the notable efforts of Beaufort’s Charlton Ogburn (1911-1998) to show that Stratford-on-Avon’s William Shakespeare did not write the epic works that are widely attributed to him.

Consider, for example, that William Shakespeare of Stratford, a man of modest birth and a minor actor in the theaters of his time, left a dreary and confused Last Will and Testament that, contrary to the custom of writers at the time, made no mention of the rights to any intellectual property to be bequeathed, such as those to the 38 plays and 154 sonnets that are commonly attributed to his authorship and that are widely considered to be the greatest body of work from one hand yet written in the English language.

Consider also that while Shakespeare’s plays demonstrate clearly their formally educated author’s close familiarity with northern Italian cities, the conduct of military affairs, the intrigues of courtiers, the way of life aboard contemporary sailing ships, the intricacies of the British Common Law, and a solid grounding in the Greek and Roman classics, Stratford’s William Shakespeare is known never to have traveled to Italy, never to have attended the Royal Court, never to have fought in war, never to have studied the classics, never to have boarded a sailing ship to go anywhere, nor to have ever even darkened the door to a courtroom.

Yet we have all learned in school that the enigmatic man from Stratford-on-Avon, the “Bard of Stratford-on-Avon,” is the author of this extraordinary body of work, and indeed the British town, Stratford-on-Avon, does a big business in memorializing William Shakespeare’s life and work. Moreover, the livelihoods of countless scholars (the “Stratfordians”) depend upon the Stratford man being “The Bard.” And if it were to be convincingly shown that he was not, theirs and millions more books chronicling various aspects of Renaissance literature would be bound for the dump.

Yes, Shakespeare is a modern day industry, and in dollars and cents (and British Sterling) the annual stakes – a.k.a. revenues — are high indeed.

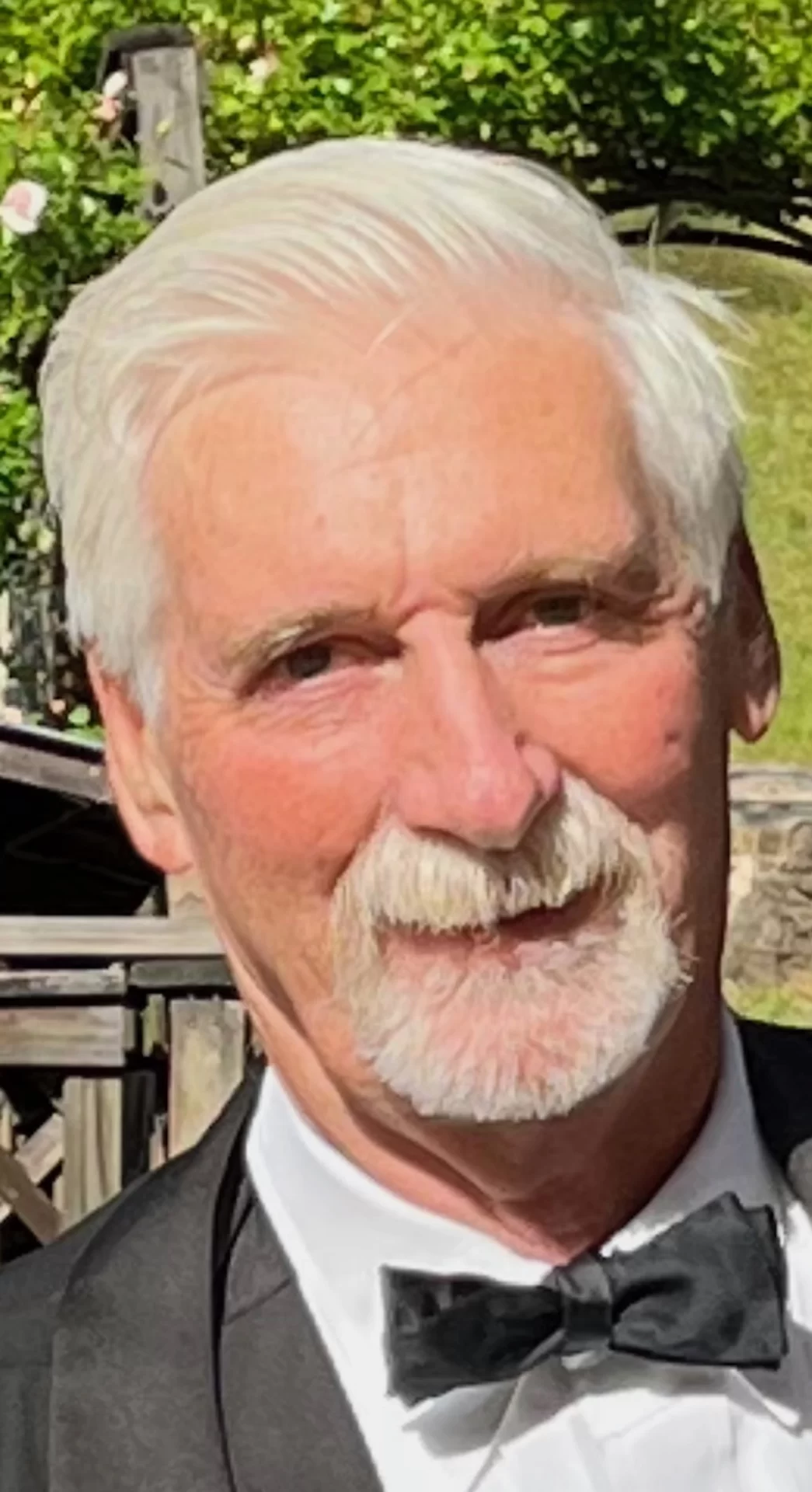

Enter, in 1984, the dog in the Stratfordian manger: Charlton Ogburn of Beaufort, South Carolina, soldier, military intelligence officer, career diplomat, literary detective, blockbuster author of “The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and Reality,” and patron saint of the “anti-Stratfordians” who are called now the “Oxfordians.”

Ogburn’s 912-page tome laid out the Stratford man as one who was unknown as a writer to his contemporaries, including his children. Ogburn exhaustively replaced him as The Bard with Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, who was said by his contemporaries to be the most gifted poet and playwright of his time even though no plays and only two poems are publicly attributed to him.

In a meticulously researched passage Ogburn showed, for example, that de Vere spent a year in the very towns in northern Italy in which, for example, “The Merchant of Venice,” “Othello,” and “The Taming of the Shrew” are set. He showed also that de Vere faced the Spanish in the Netherlands as Commander of the Horse in 1585, studied law at one of England’s foremost legal academies and served in the British House of Lords – England’s premier lawmaking body at the time – for 40 years. Moreover, to get from his castle in the north of England to London, which he did frequently to attend House of Lords meetings, it was necessary for de Vere to book passage regularly on commercial sailing ships.

That’s not all. The two poems publicly attributed to de Vere, and written early in his life, resonate remarkably in the way of The Bard’s unmistakable voice.

But how familiar was de Vere with the ways of courtiers?

After his father died when he was 8 years-old, de Vere was raised by Lord Burghley, the consummate political operative of his time. Burghley, later known for his tight control over the Crown’s finances and intelligence services, would serve as Principal Secretary — or what we would call today “Chief of Staff” — to “the virgin queen,” Elizabeth I, for most of her 44 year reign. When he came of age de Vere married Burghley’s daughter and throughout their lives they were regulars in the Royal Court where de Vere’s well-known nickname was “Spear Shaker.”

There’s more: familiar with the ways of the Royal Court indeed.

The most substantial and spectacular scholarship offered by Oxfordians since Ogburn’s 1984 work has been contributed by Alan Tarica and can be readily viewed on his website at https://sites.google.com/site/eternitypromised/ . Tarica studied extensively the Bard’s 154 sonnets (first published in 1609 as a group, five years after de Vere’s death in 1604 and seven years prior to Shakespeare’s death in 1616) and discovered that if they are read in reverse order, that is from 154-to-1, they constitute a series of entreaties from de Vere to Elizabeth I urging her to recognize their illegitimate son, the young man raised Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton.

If Ogburn in his “Myth and Reality” explained powerfully the “what” but fell short a bit on the “why,” arguing accurately (but perhaps under the circumstances somewhat hollowly) that play-writing was widely-regarded as an activity too déclassé for Elizabethan noblemen to admit spending their precious time upon, Tarica has broken the “why” question wide open.

His illegitimate son thesis reveals starkly the motive for the Crown’s resolve to keep Edward de Vere and his work, no matter how brilliant, under the royal covers. Likewise there were compelling reasons for Elizabeth’s successor to the throne, her distant cousin King James I, the first of the Stewarts, to perpetuate the cover-up. Revealing Wriothesley as the Queen’s natural son and thus the true successor to the Tudor throne would have caused royal chaos, and most certainly a challenge to James’ right to rule as King of England.

Those who consider all this implausible might remind themselves that the virgin queen’s father, Henry VIII, discarded with impunity five wives before himself dying a natural death as monarch while married to a sixth.

Did William Shakespeare of Stratford-on-Avon – the son of a glove-maker and a bit part actor who happened to have a convenient surname – cooperate to the extent required in the royal scheme? Of course, say the Oxfordians. His choice was no choice: cooperate … or else.

Who now doubts, as Charlton Ogburn argued thirty years ago, that de Vere was spectacularly positioned to describe in intimate detail the rivalries, illicit romances, glories, disappointments and other personal dramas of courtiers?

Alan Tarica, speaking of Charlton Ogburn last week said, “While Charlton is not the most famous anti-Stratfordian, he is very arguably the most influential. I hope one day he receives the recognition he deserves.”